There is close to $1 trillion worth of subprime paper valuations in U.S. private tech stocks. This is not going to end well.

Almost half the unicorns have fake and misleading valuations. Some companies valued at more than $1 billion have made such generous promises to their preferred shareholders that their common shares are nearly worthless, according to new research.

Private investors are sobering up to the fact that more than 90 percent of private tech valuations are fake and don’t rely on successful IPOs, cash, or profits but rely instead on fake valuations and finding a bigger fool to keep the Ponzi scheme going.

There’s a widening disconnect between bearish tech funding trends, weak IPO volume, bubblelicious valuations, misleading representations to investors, weak IPO performance and Nasdaq record highs. This disconnect tells the story of a set-up for very profitable trades for those who can recognize and exploit this market disconnect at the right time.

If there is a severe crash in private tech that feeds on itself, there is one stock that stands out that you probably want consider for short exposure or a hedge.

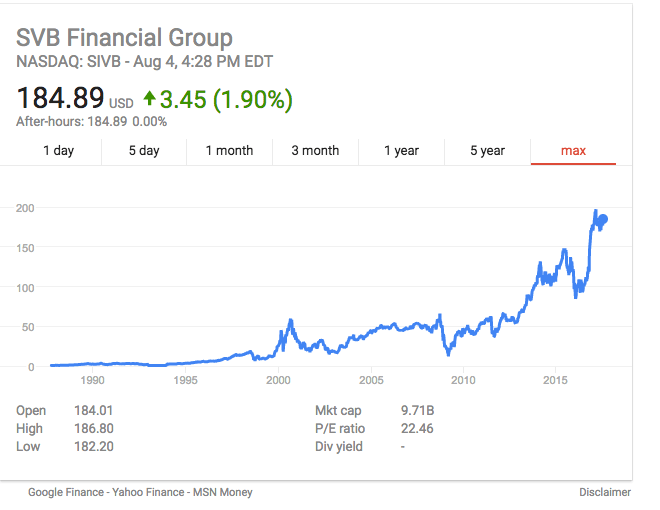

Silicon Valley Bank or SVB Financial Group (SIVB) is the hometown bank of private tech. It’s the banker of choice in Silicon Valley and as frothy unicorn valuations have risen, so has its stock.

Seed-stage financing for startups has slowed down 40 percent since the peak in mid-2015, Reuters reported last week. Although the Nasdaq has gained 21 percent year-to-date and 25 percent over the last 12 months, the Sharepost 100 Fund — a proxy for private tech — is down 4.6 percent YTD and down 2 percent over the last 12 months.

Because the IPO door is largely closed to private tech companies, they rely on more speculative funding rounds or hopes of getting acquired rather than conventional business protections of profits and cash flow.

Similar to the instruments in the subprime crisis, private tech has a lot of mark-to-mystery qualities where the accounting ranges from creative to outright fraudulent. The term is often used behind closed doors with this no-revenue formula. It’s a play on the common term for a more logical investment practice called mark-to-market, which is used to create a realistic appraisal of a company’s financial assets.

“VCs can create this mark-to-mystery valuation because as long as there are no numbers, I can have whatever mark I want for an external valuation of a startup,” said venture capitalist Paul Kedrosky.

Kedrosky explained the problems with the private tech sector this way:

“It serves the interest of the investors who can come up with whatever valuation they want when there are no revenues,” said Kedrosky, a venture investor and entrepreneur. “Once there is no revenue, there is no science, and it all just becomes finger-in-the-wind valuations.”

How much “fake valuation” paper is out there in private tech? What happens if the music stops and there are no IPOs, no big exits, no more venture debt, and no new funding for the paper underneath these companies?

The paper valuations underneath these mostly unprofitable companies could be more than $1 trillion. As so-called unicorns — those startups valued at $1 billion or more — are thought to be valued close to $700M in aggregate (U.S. only).

Almost half of unicorns have fake and misleading valuations, according to Will Gornall and Ilya Strebulaev, two professors at Stanford University and the University of British Columbia. These are some findings from their research:

We found that the average highly-valued venture capital-backed company reported a valuation 49 percent above its fair value. But, when the valuation was recalculated using the financial model developed by Ilya and I — which derives a fair valuation of each class of shares of VC-backed companies by taking into account the intricacies of contractual cash flow terms — almost half of these companies lost their unicorn status, with 11 percent being overvalued by more than 100 percent. Some unicorns have made such generous promises to their preferred shareholders that their common shares are nearly worthless.

This is happening because current valuations make a misleading assumption: that a company’s shares have the same price as the most recently issued shares. This oversimplification significantly inflates valuations, since the most recently-issued shares almost always include perks not found in previously-issued shares.

Specifically, we found that 53 percent of unicorns gave their most recent investors either a return guarantee in IPO (14 percent), the ability to block IPOs that did not return most of